public health

Predicting COVID-19 Risk in the U.S.

By Maximilian Marshall and Lauren Gardner

September 3, 2020

Summary

In an effort to help governments and individuals with decision making related to the COVID-19 outbreak, the CSSE has developed a risk model at the county level for the United States. Using epidemiological data from our publicly available map and repository, along with anonymized mobile phone data, demographic and socioeconomic information, and various behavioral metrics, we are able to accurately assess the risk presented by COVID-19 in the United States at local, state, and national levels.

Motivation

COVID-19 presents an ongoing public health emergency. In the United States, government and societal responses to the virus have been inconsistent, both over time and in different regions within the US. Besides creating a turbulent and dangerous environment for viral transmission, these inconsistencies in policy and behavior have also made accurately anticipating the spread and effects of the disease difficult. The potential for asymptomatic transmission and a relatively long incubation and infectious period mean that behavior in the weeks prior play an important role in making effective epidemiological predictions for the future. Additionally, risk at a particular location is not just determined by the internal policies and behavior within that location; any other place that it is connected to by human mobility is also a potential source (or destination) of risk. For example, lax social distancing practices in one particular city (i.e. opening bars and restaurants for indoor use) could contribute to infections in multiple other parts of the US, depending on who visits that city and where they go after. Accurately capturing these factors and generating a robust analysis is complex and time-consuming, and many local and state governments are already resource-constrained by the health and economic effects of the virus. Given the broad range of decision makers and varying responses needed in the face of the rapidly evolving outbreak, we constructed our routine using a flexible approach that allows us to model different risk indicators for different use cases. While we believe that predicting absolute case numbers is valuable, we also believe that predicting events like case spikes in vulnerable places is extremely important. There is not a one size fits all metric to understand and respond to the danger that the COVID-19 presents. For example, weekly case growth is important for short-term distribution of hospital supplies, while longer-term predictions are more helpful for planning school reopening policy and vaccine distribution. Since different types of predictions are necessary, we developed a flexible modeling framework to synthesize the complex spatiotemporal dynamics of human behavior and viral transmission into accessible and accurate predictions at the local level. We continue to refine the model to both increase the accuracy of our predictions and infer the most important factors driving the outbreak.

Methods

Our risk modeling framework uses an empirical, statistical methodology to forecast COVID-19 risk for the United States. We model several different aspects of the outbreak, including new cases and deaths over different time horizons, whether or not case and death curves will significantly deviate from current trends, case and death rates per person, risk categories based on time-dependent rates of change, and categorical epidemiological classifications. These examples demonstrate our modeling philosophy, and the value of our risk analysis. Our goal is to continue to develop the model to better identify at-risk populations and learn who and where people are most exposed to risk of infection and death from COVID-19.

Our forecasting model utilizes an empirical machine learning (ML) approach centered on a simple idea, that future viral infections are driven by how individuals respond to and spread the current outbreak, and future deaths are the result of the intersection of infections and vulnerable populations. We directly model this by using the real-time and time series data on COVID-19 infections and deaths from our dashboard, granular cell phone mobility data, and demographic information from the US census and other publicly available sources. Our approach combines disparate data inputs into a meaningful predictive model using a combination of raw data and novel metrics generated in-house as inputs. We use different statistical methodologies, such as multiple linear regression, logistic regression, random forest regression/classification, and curve fitting, and are developing techniques to further improve predictive capabilities with ensemble approaches, input clustering, and deep learning.

Risk Factors Considered

As referenced above, our methodology involves both synthesizing our own predictor variables and using raw data. An example of a synthesized variable is our mobility metric, which takes raw mobility numbers and generates a value that can be used as a proxy for social distancing. Other synthesized inputs, for example, combine mobility and case data to flag potential routes for viral spread and examine the intersection of rising cases and higher-age populations. We use different combinations of these inputs, as well as other raw data sources, depending on the particular analysis we perform. We are also evaluating and hope to include additional behavioral variables in the near future, which would reflect individual decision making such as compliance with recommended social distancing policies, mask usage, and hand washing. We believe capturing this behavior is an important part of understanding the outbreak, but want to ensure that available information meets our data standards before we include it in the model. Information on our current input data is included below.

Epidemiology Data

COVID-19 case and death data are taken from the JHU CSSE COVID-19 dashboard, which includes outbreak information at the county level, updated daily, starting on January 22, 2020.

Mobility Data

We use anonymized mobile phone location data from SafeGraph to capture human mobility and generate metrics related to the likelihood of viral spread. Mobility counts are cleaned and normalized to represent population-level movements as closely as possible.

Population and Health Indicators

We gather this information from several publicly available sources. Population totals, demographic percentages, and age breakdowns come from the US Census. Health and economic measurements such as smoking percentages, poverty, and chronic disease are sourced from County Health Rankings. Statistics on hospital beds and availability come from the Definitive Healthcare Dataset published by ESRI. We are actively pursuing and testing additional population health metrics, both to improve predictions and enhance our ability to explain outbreak dynamics.

Example Outputs

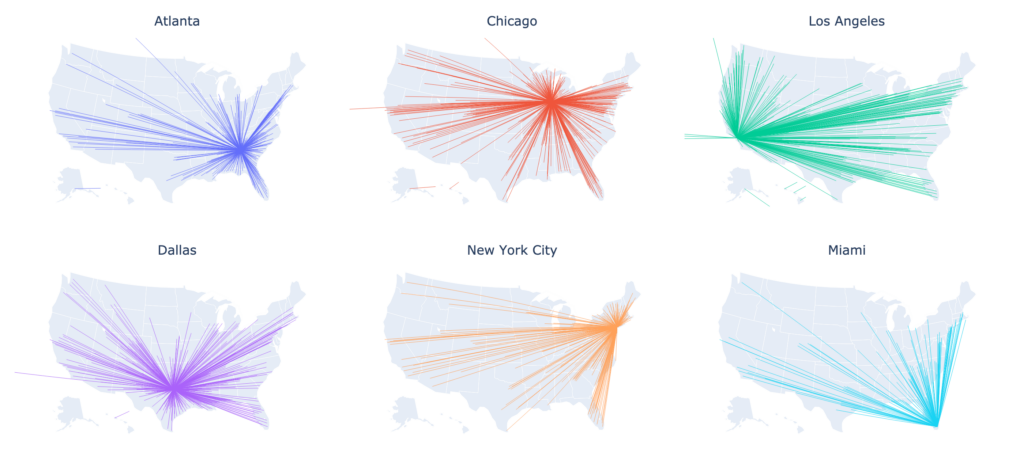

The maps below demonstrate the output of a model run that predicts risk categories based on how many new cases will appear in each county in the US. This specific example displays the predicted risk category for the first two weeks of August, and the actual categories from observed data.

Comparison of projected quantiles of new cases in each county during the first two weeks of August 2020 (output from the model), compared to observed cases reported.