[vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”scroll-down-row” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_raw_html]JTNDZGl2JTIwY2xhc3MlM0QlMjJzY3JvbGwtZG93bi13cmFwJTIwbm8tYm9yZGVyJTIyJTNFJTNDYSUyMGhyZWYlM0QlMjIlMjMlMjIlMjBjbGFzcyUzRCUyMnNlY3Rpb24tZG93bi1hcnJvdyUyMCUyMiUzRSUzQ3N2ZyUyMGNsYXNzJTNEJTIybmVjdGFyLXNjcm9sbC1pY29uJTIyJTIwdmlld0JveCUzRCUyMjAlMjAwJTIwMzAlMjA0NSUyMiUyMGVuYWJsZS1iYWNrZ3JvdW5kJTNEJTIybmV3JTIwMCUyMDAlMjAzMCUyMDQ1JTIyJTNFJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTA5JTA5JTA5JTNDcGF0aCUyMGNsYXNzJTNEJTIybmVjdGFyLXNjcm9sbC1pY29uLXBhdGglMjIlMjBmaWxsJTNEJTIybm9uZSUyMiUyMHN0cm9rZSUzRCUyMiUyM2ZmZmZmZiUyMiUyMHN0cm9rZS13aWR0aCUzRCUyMjIlMjIlMjBzdHJva2UtbWl0ZXJsaW1pdCUzRCUyMjEwJTIyJTIwZCUzRCUyMk0xNSUyQzEuMTE4YzEyLjM1MiUyQzAlMkMxMy45NjclMkMxMi44OCUyQzEzLjk2NyUyQzEyLjg4djE4Ljc2JTIwJTIwYzAlMkMwLTEuNTE0JTJDMTEuMjA0LTEzLjk2NyUyQzExLjIwNFMwLjkzMSUyQzMyLjk2NiUyQzAuOTMxJTJDMzIuOTY2VjE0LjA1QzAuOTMxJTJDMTQuMDUlMkMyLjY0OCUyQzEuMTE4JTJDMTUlMkMxLjExOHolMjIlM0UlM0MlMkZwYXRoJTNFJTBBJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTIwJTA5JTA5JTA5JTIwJTIwJTNDJTJGc3ZnJTNFJTNDJTJGYSUzRSUzQyUyRmRpdiUzRQ==[/vc_raw_html][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”full_width_background” full_screen_row_position=”middle” equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” bg_color=”#f7f7f7″ scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”section-top-padding section-bottom-padding” id=”read-more” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”padding-5-percent” column_padding_position=”all” background_color=”#ffffff” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” top_margin=”0″ bottom_margin=”0″ el_class=”about-content-col” width=”1/1″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][tabbed_section style=”default” alignment=”left” spacing=”default” tab_color=”Accent-Color” el_class=”custom-research-data-mining-tabs”][tab icon_family=”none” title=”Tracking global bicycle ownership patterns” id=”1532330197-1-24″ tab_id=”1532330313539-3″][vc_column_text el_class=”custom-split-line-heading”]

Tracking global bicycle ownership patterns

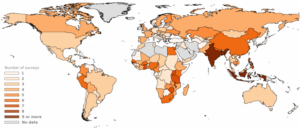

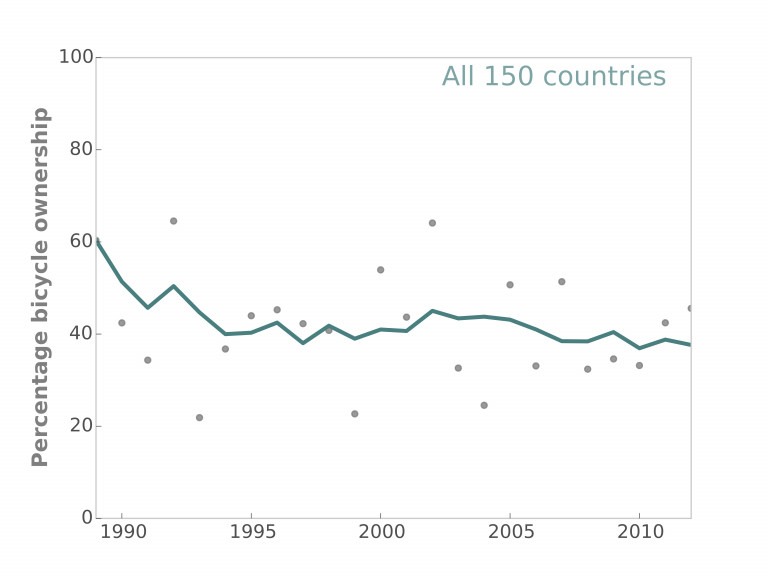

In the first effort on this scale, we sourced data from 11 types of surveys spanning a period of 23 years (1989 – 2012) and covering 150 countries.

Map showing number of survey sources for each country in bicycle ownership dataset

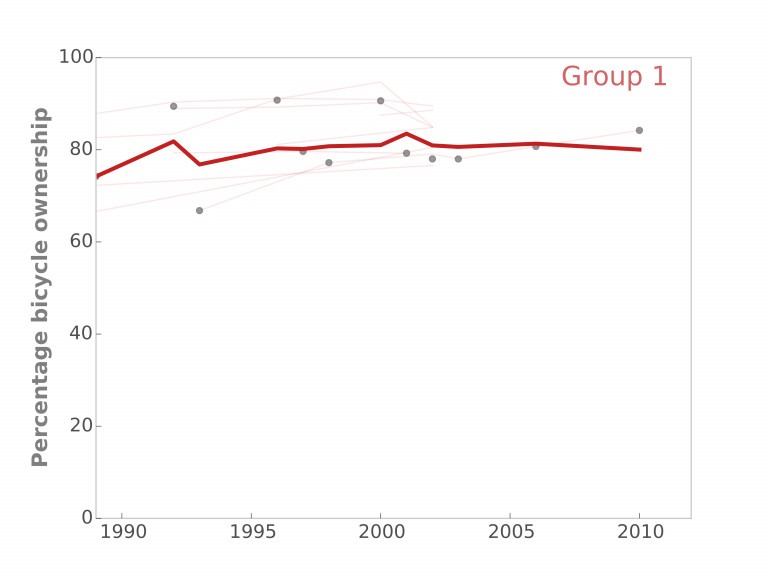

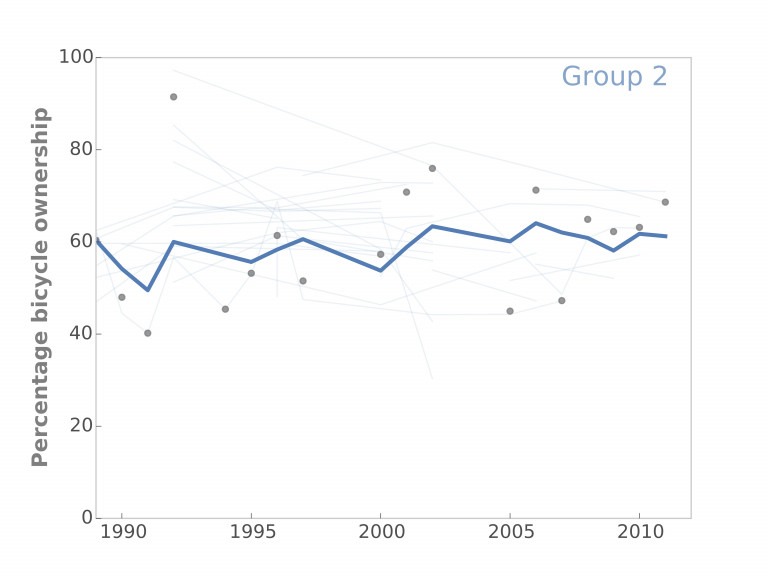

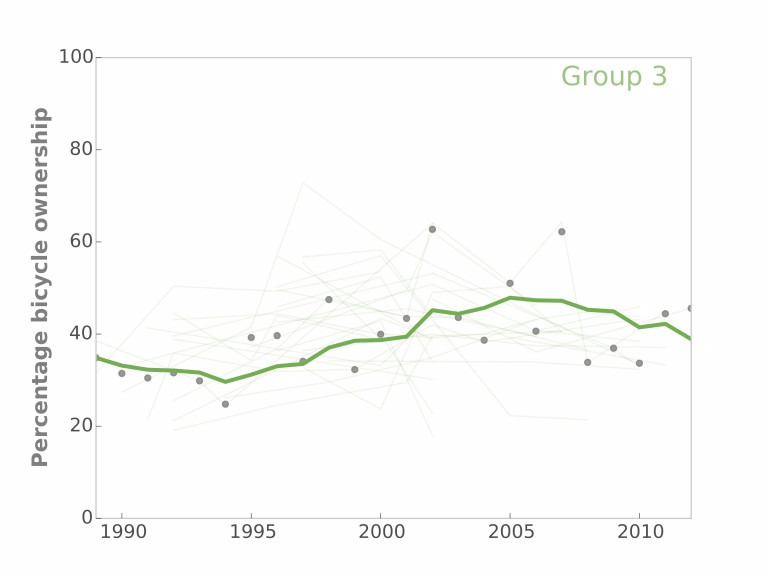

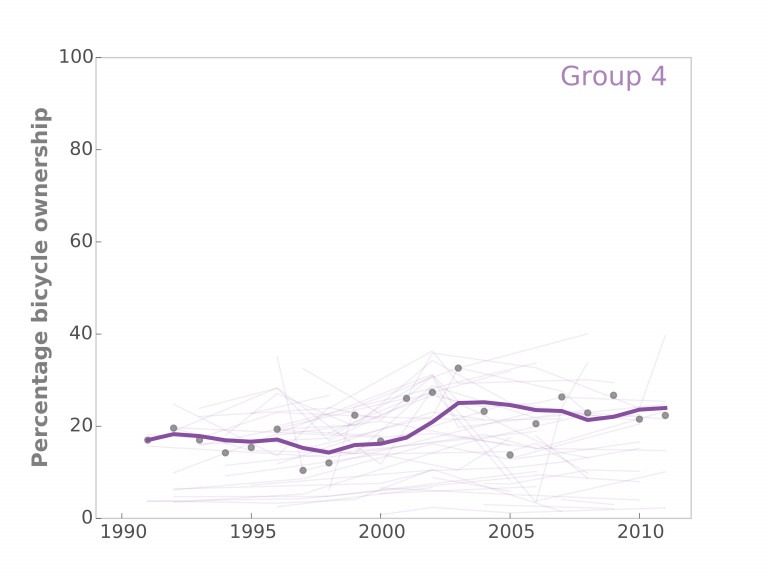

Given that the data were sparse, we applied unsupervised learning to discover any underlying patterns that might useful to researchers and other stakeholders in sustainable active transport. Using a suite of methods: dynamic time warping (data alignment), the gap test (optimal cluster numbers) and hiearchical agglomerative clustering, we found four prevailing groups of characteristic ownership levels.

To find the group trends, we used the weighted average rolling mean over a five-year window. Extrapolating from the 1.25 billion households represented in the surveys we mined and the common question of interest: “Does your household have at least one bicycle?” we estimate that 580 million or more bicycles were available to the world’s households as of 2012.

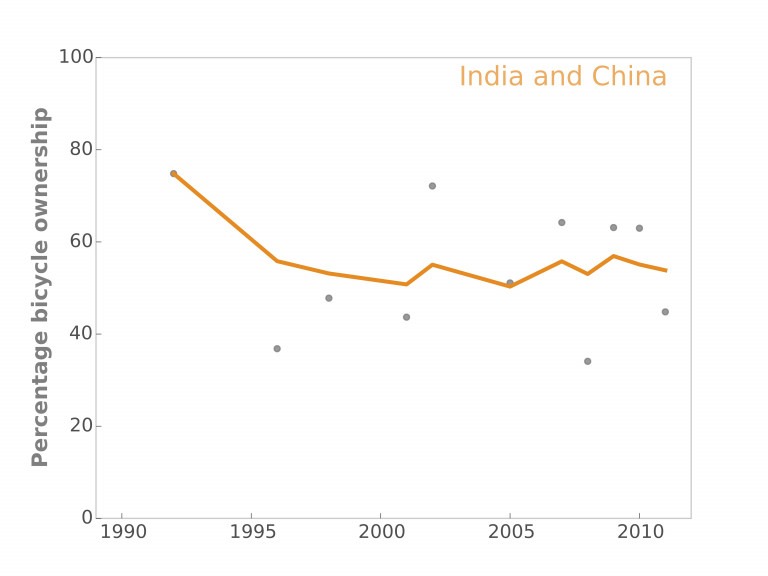

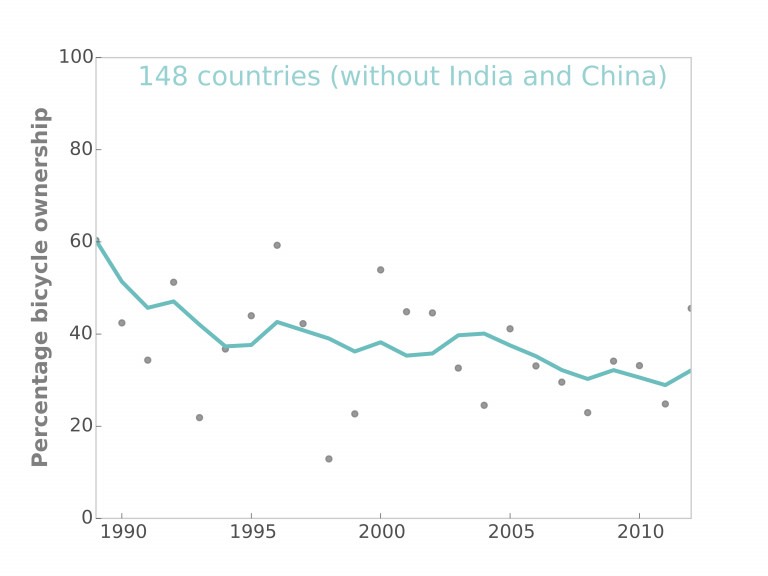

Finally, we shed light on aggregate global trends in ownership, with a spotlight on India and China, as they together account for a quarter of the world’s households. We conclude that globally, bicycle ownership has not been on the rise.

[/vc_column_text][/tab][tab icon_family=”none” title=”Map of bicycle ownership” id=”1532330197-2-9″ tab_id=”1532330313580-2″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/tab][tab icon_family=”none” title=”Trends in bicycle ownership” id=”1532335726585-2-5″ tab_id=”1532330313580-2″][vc_column_text][/vc_column_text][/tab][/tabbed_section][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”middle” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” top_padding=”30″ disable_element=”yes” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”2/3″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text]This work has been published as Tracking global bicycle ownership patterns in the Journal of Transport and Health, which highlights work at the transport-health nexus. Click here to view the paper on ScienceDirect. Download it here.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”1/3″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][image_with_animation image_url=”7027″ alignment=”right” animation=”None” border_radius=”none” box_shadow=”none” max_width=”100%”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row type=”in_container” full_screen_row_position=”middle” equal_height=”yes” content_placement=”top” scene_position=”center” text_color=”dark” text_align=”left” class=”section-top-padding ” overlay_strength=”0.3″ shape_divider_position=”bottom” shape_type=””][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” el_class=”custom-split-line-heading” width=”1/4″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][split_line_heading]Relevant

publications

[/split_line_heading][/vc_column][vc_column column_padding=”no-extra-padding” column_padding_position=”all” background_color_opacity=”1″ background_hover_color_opacity=”1″ column_shadow=”none” column_border_radius=”none” width=”3/4″ tablet_text_alignment=”default” phone_text_alignment=”default” column_border_width=”none” column_border_style=”solid”][vc_column_text css_animation=”fadeInUp” el_class=”visual-generated-div”]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]